Tie Your Shoes

When you attend a literary gathering, such as the annual Sewanee Writers’ Conference in Tennessee, as I have this summer, taught by learned professors from all over, one of the common variables that emerge is that of shoes. I live in New York City and even though men no longer snap on spats in the evening and most women aren’t mincing along Madison Avenue on skyscraper-tall alligator stilettos, still, the footwear you find people wearing in Manhattan is far superior to that worn mostly by visiting and resident faculty members. I can’t comment on the fulltime students, because they’re not yet in attendance on campus.

I think one of the reasons I never considered a career in academia is because I cannot endure the thought of slipping on a pair of oyster-gray rubber Crocs that elicit a deflating squish with each stride, toes squirming like panicked fish through the air holes, or pulling up a pair of faded white athletic socks and strapping a Byzantine network of sandal straps around them. I hope not to have to wear Velcro-secured shoes until much later in my life or to ever sport a pair of backless scuffs that reveal, tongue-like, the alkaline-white of middle-aged heels. And I don’t want to appear as a phosphorescent-hued primate padding along in Skele-Toes (footwear akin to the Creature from the Black Lagoon). I like shoelaces, which are not found on the feet of professors and MFA and PhD. candidates.

There’s the issue, too, of socks, most wearers of which favor the polyester thread count over the cotton one; the elasticity has long burned away from too many dryer cycles. Those poly-cotton blends droop below the bottom of pants legs, often revealing a bone-white flank of the lower ankle. And why all of these earth-tone shades of socks, instead of just black or blue? Something about the academic life that requires the wearing of bad shoes and socks.

Then there’s the one participant at the conference who only goes barefoot, indoors and out, even when we take long walks on rocky forest trails. He is a middle-aged man, a self-described “hillbilly lawyer.” But, surprisingly, when I summoned up the courage to look at his feet, expecting to see unraveling taupe bandages that ring many a professorial toe here or the traffic-light amber (or, green) of nails or a pinkie so curled under as to evidence an evolutionary shift, his feet were unmarked and strong; they were cleaner, in fact, than others’ in this gathering of name-brand novelists and poets.

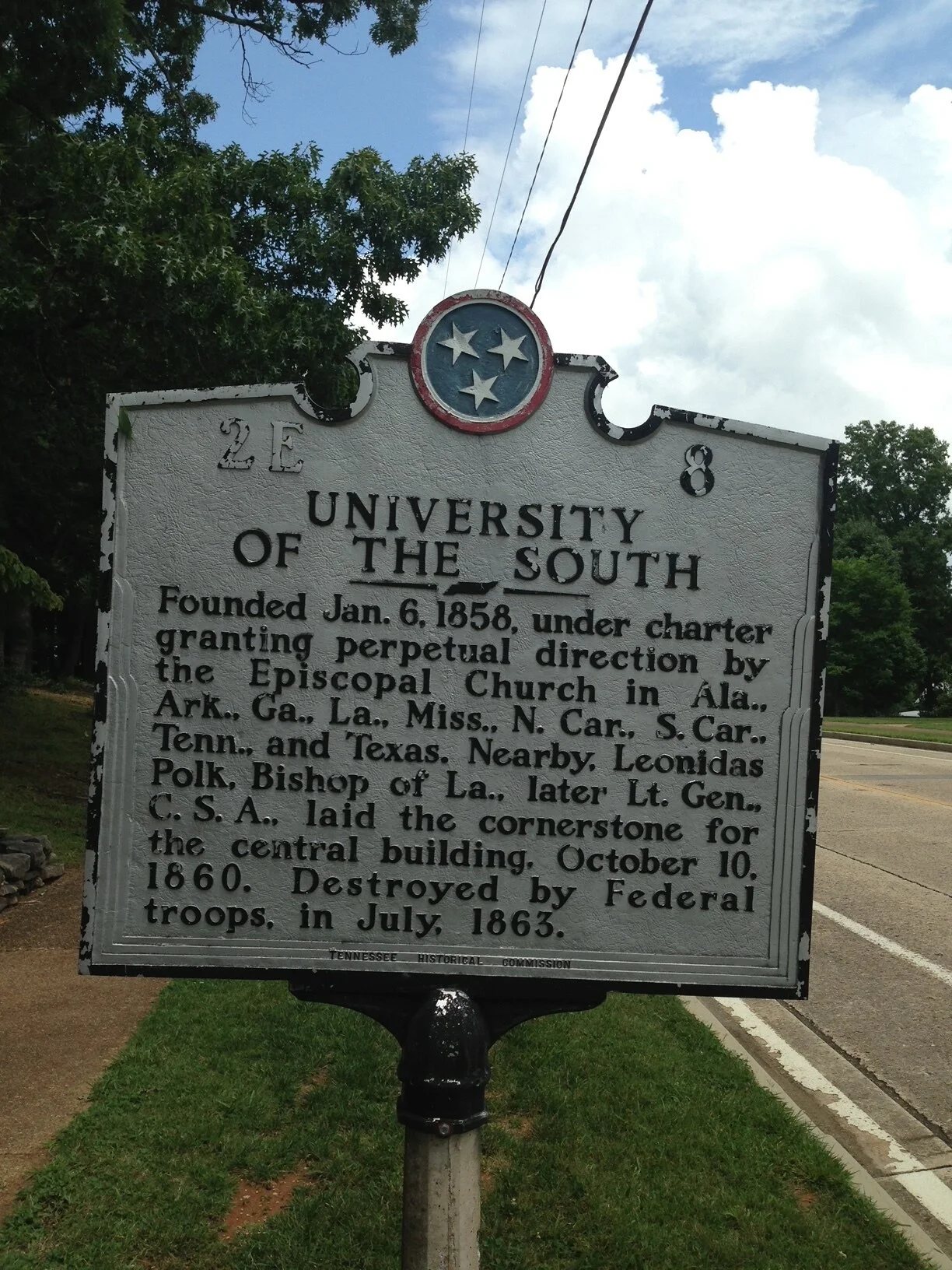

At each conference event I attend, particularly the evening cocktail gatherings at one of the handsome university buildings fashioned of quarried Tennessee stone, several of my fellow attendees comment on my shoes. I wear simple, polished brown or black chukkas—though I also have a pair of brown suede ones, too—which seems to surprise the other students so much that that they often look down and remark, “So spiffy.” Or, “I can practically see my face in the hide.” (The cufflinks I secure on my shirts, don’t help with my image.) To some, I’m known as the man with the good shoes. I wish I was known as the one with the good poems, but hark, alas, that is not the case.

An accomplished Romanian-born fiction writer and poet, Alta Ifland, said at the breakfast table that there was a relationship between points on the feet and sexual passion (the tablecloth prevented me from seeing what she was wearing). Perhaps the discipline of reflexology addresses such theories. But when I see the feet and shoes of my fellow attendees and famous guest lecturers, even those of the young dashing ones, with tenures and scholarly books to their credit, I feel more of an urge to produce a couplet than seek a coupling.